Transcription:

Comparison of the Wisdom and Works of God and Man

By Anna Reynolds-College-July 11, 1846

(Copied by Josephine Yancey)

(Given by John Ardis Manry. Aug. 6, 1930)

How narrow to its utmost extent is human science, how circumscribed is the sphere of intellectual exertion. Man spends his life acquiring knowledge, and yet how little does he know. The farther he attempts to penetrate the secret recess of nature, the more he becomes bewildered and benighted. Beyond a certain limit all is mere conjecture and confusion; so that the advantage of the learned over the ignorant consist (sic) chiefly in having ascertained how little is to be made known to man. It is true that he can measure the sun and compute the distance of the planets, he can even calculate their periodical movements, and even ascertain the laws by which they perform their sublime revolutions; but with regard to their constitution, and the beings which inhabit them, he knows nothing. Delighting to examine the economy of nature, in our own world, he has analyzed its elements and given name to them respectively, and yet he is as much at a loss to determine that particular character of oxidation, called combustion, is attended by heat, or to say while the pressure of Calorie (sic) causes liquidity of water, as they are who have never devoted themselves to science. He has discovered that all bodies unsupported fall to the ground, and is [page 1] taught to account for it by the laws of gravitation.

And what does he gain by this more than a term? Does it convey to the mind any idea of that mysterious and invisible claim which draws all things to a common centre? He observes the effect, gives name to the cause and yet he can neither explain nor comprehend the cause of it. His thoughts ascend to loftier objects and he indulges in metaphysical speculation. And here, while he perceives the two distinct existences, and matters and mind. (sic) He is baffled in every attempt to understand their mutual dependence and mysterious connection. How many years of his life are devoted to the acquisition of languages, by means of which he many explore the records of ages past and remote, and became familiar with the learning and literature of other times. (sic)

And what does he gather from these laborious researches, but the conviction of his own weakness and ignorance and the mortifying consciousness that man is ever struggling with his our (sic) importance vainly endeavoring to overleap his bounds, which limit his anxious inquiries. How little has man in his best estate of which to boast and what folly in him is glory, in his narrow capacities, and to value himself upon his unpleasant acquisitions.(sic) Such too is the limit assigned, by weariness from labor, and by depth, to the power of man that it is very difficult to attain perfection in any science. Even men of splendid genius and enlarged attainments know [page2] very little in comparison to what might be learned in a protracted lifetime or by incessant application.

In the same degree that his knowledge is deficient, his works are imperfect. We had only to compare them with the work of God to ascertain their inferiority. Man's works are only the imitation of those of nature, and is poor and inferior. Nature is rich and various. In the natural kingdom we find an inexhaustible treasure; everything presenting to the mind a new and interesting subject.

But with art it is not so, there the objects are comparatively small, and the more minutely they are examined the more numerous the faults and imperfections which we discover in them. And what is their duration? They are destroyed and forgotten, while those by nature remain for untold ages as perfect as when created. The most ingeniously and skillfully constructed machine, in the construction and perfection which man has spent many months, or years of toil and labor whose complicated mechanism, has called forth the utmost energy of mind is a toy compared with any, even the simplest works of nature. Constantly requiring repairs it grows unfit for use, and soon ceases to answer its intended purpose.

These irregulations (sic) and imperfections are present from the very first construction for no artist, however eminent can forsee (sic) all the changes which his work undergoes or be able to provide against them. The most enduring machine, the most stately edifice and the proudest works of man, last but a few years and then decay and pass [page 3] away. But not so the works of God - nothing is lost, nothing perishes in nature and though her works may disappear from the sight of man, they are not destroyed, but transformed into the objects of her handiworks, there continuing in existence.

And how many years of the results of man's ingenuity are unfit for use, serving only to amuse. It is not so in nature. There all things exist for a certain purpose, accomplishing the ends, for which they were designed and created. But God's wisdom is unlimited. The various creations which inhabit the earth and fill the air and water; the depths of space, and the many twinkling stars and planets and orbs, that hold their places in the vaults of might's dominion all proclaim the wisdom of God.

Were it granted to mortals to know the concatenation of causes in nature, how great would be our admiration!, (sic) however incapable we are of forming an inadequate idea of the whole of God's works, the little we perceive of them gives no reason for acknowledging his wisdom. But to be convinced that He is indeed wise, we need not have recourse to extraordinary events or wonderful manifestations of his skill and power, for it is proven to us in the most forcible manner by the very common occurrences, and by the daily changes which are effected in nature. Nothwithstanding (sic) [page 4] his majesty and grandeur. He does not disdain to pay attention to the weakest creature which exists, from the elephant to the mite, all animals are indebted to Him for their life, habitation and nourishment. Nature is always acting even when she appears to rest - and she renders us real services when she seems to refuse them.

We cannot turn our eyes on any side, without seeing innumerable objects which have connected with them some inseparable attribute which shows God's wisdom for whether they be great or small the skill and forming hand are His. The starry is (sic) an admirable theater of the wonder of the most High, Their (sic) multitude of splendor under them, a most magnificent spectacle, while their order and grandeur affords topics for the sublimest (sic) thoughts. What can be more beautiful and majestic than the immense expanse of the heavens illuminated by lamps without number glowing the more brightly from the darkness out of which they shine (sic). To name the immense bodies dispersed through vast space, is sufficient to excite astonishment and admiration at the majesty of the workman. In the centre of our system of worlds the Sun (sic) has established his throne, and around him at uniform distances, and in certain periods of time revolve the planets.

But the whole system including the sun and his planets, is but a point in the expanse of nature. We behold innumerable stars, which though they appear to us small, are probably equal [page 5] to the Sun (sic) in dimensions and splendor, and they may be not only worlds, but centres of planetary systems (sic). Human intellect cannot determine the design for which these bodies were created; but without doubt they have sublime ends, and each of them a suitable and particular destination and they may be inhabited as our earth with intelligent and rational beings.

However surprising these observations may be, we do not yet reach the limits of Creation. If we could dart beyond the moon and approach the planets, if we could leave the Sun behind and approach the most distant stars, we might still discover new orbs and new systems of worlds, perhaps more and more magnificent and yet these would not fix the bound of the empire of the Creator. How vast, how unlimited must be the wisdom of Him who has created these worlds and who regulates and supplies them. They have never in the course of their revolutions of thousands of years come into contact nor interrupted each others (sic) motions. The fixed stars are now relatively situated as they were thousands of years ago, their distances never varying. What power has fixed them, in their lofty place and what retains them in those positions?

It is of God the Creator of all things whose wisdom has devised means of supporting them each in its proper bounds, and [page 6] these means continue unbeknown to man, undiscovered by the sublimest (sic) genius, and they forever remain a mystery;

"But chief of all his works, since time began,

He summoned to life, and named it Man.

A wondrous frame; of dust he made the whole,

And breathed into the clay a living soul,

With intellect endered and powers of sense

To scan the wonders of omnipotence." *

There is perhaps no work which demonstrated the wisdom of God more than the Creation of Man, the perservation (sic) of his life, and the adaption of all the works of nature to his comfort and enjoyment. The millions of human beings dispersed in different nations over the earth, are provided with everything necessary to supply their wants and render life comfortable. The greater the number of men is, the more their wants are varied, according to their conditions, ages and manners of life, and the more incapable are we of forming a plan which will embrace every case of taking the necessary precautions for the preservation of life; and consequently the more should those arrangements, full of goodness and wisdom, which our Creator has made for this purpose, deserves our attention and admiration. All things teach the wisdom of God - we can cast our eyes on no side, but we are made more clearly conscious that this great attribute of Diety (sic) is upon all nature.

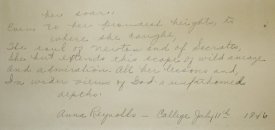

"What does Philosophy impart to man,

But undiscovered wonders; Let [page 7] her soar,

Even to her proudest heights, to where she caught,

The soul of Newton and of Socrates,

She but extends this scope of wild amaze

And admiration. All her lessons and,

In wider views of God's unfathomed depths."**

Anna Reynolds - College July 11th, 1846

Notes:

* "But chief of all his works, since time began,

He summon'd to life, and nam'd it Man:

A wondrous frame! Of dust he made the whole,

And breath'd into the clay a living soul;

With intellect endued, and powers of sense

To scan the wonders of Omnipotence."

Original text of the poem by Mrs. Clark's Lines on Reading Strum's Reflections (Bristol, March 12, 1801)

** "What does philosophy impart to man

But undiscovered wonders?--Let her soar

Even to her proudest heights--to where she caught

The soul of Newton and of Socrates,

She but extends the scope of wild amaze

And admiration. All her lessons end

In wider views of God's unfathom'd depths."

Excerpt from Henry Kirke White's poem entitled "Time, A Poem [1]"

By Anna Reynolds-College-July 11, 1846

(Copied by Josephine Yancey)

(Given by John Ardis Manry. Aug. 6, 1930)

How narrow to its utmost extent is human science, how circumscribed is the sphere of intellectual exertion. Man spends his life acquiring knowledge, and yet how little does he know. The farther he attempts to penetrate the secret recess of nature, the more he becomes bewildered and benighted. Beyond a certain limit all is mere conjecture and confusion; so that the advantage of the learned over the ignorant consist (sic) chiefly in having ascertained how little is to be made known to man. It is true that he can measure the sun and compute the distance of the planets, he can even calculate their periodical movements, and even ascertain the laws by which they perform their sublime revolutions; but with regard to their constitution, and the beings which inhabit them, he knows nothing. Delighting to examine the economy of nature, in our own world, he has analyzed its elements and given name to them respectively, and yet he is as much at a loss to determine that particular character of oxidation, called combustion, is attended by heat, or to say while the pressure of Calorie (sic) causes liquidity of water, as they are who have never devoted themselves to science. He has discovered that all bodies unsupported fall to the ground, and is [page 1] taught to account for it by the laws of gravitation.

And what does he gain by this more than a term? Does it convey to the mind any idea of that mysterious and invisible claim which draws all things to a common centre? He observes the effect, gives name to the cause and yet he can neither explain nor comprehend the cause of it. His thoughts ascend to loftier objects and he indulges in metaphysical speculation. And here, while he perceives the two distinct existences, and matters and mind. (sic) He is baffled in every attempt to understand their mutual dependence and mysterious connection. How many years of his life are devoted to the acquisition of languages, by means of which he many explore the records of ages past and remote, and became familiar with the learning and literature of other times. (sic)

And what does he gather from these laborious researches, but the conviction of his own weakness and ignorance and the mortifying consciousness that man is ever struggling with his our (sic) importance vainly endeavoring to overleap his bounds, which limit his anxious inquiries. How little has man in his best estate of which to boast and what folly in him is glory, in his narrow capacities, and to value himself upon his unpleasant acquisitions.(sic) Such too is the limit assigned, by weariness from labor, and by depth, to the power of man that it is very difficult to attain perfection in any science. Even men of splendid genius and enlarged attainments know [page2] very little in comparison to what might be learned in a protracted lifetime or by incessant application.

In the same degree that his knowledge is deficient, his works are imperfect. We had only to compare them with the work of God to ascertain their inferiority. Man's works are only the imitation of those of nature, and is poor and inferior. Nature is rich and various. In the natural kingdom we find an inexhaustible treasure; everything presenting to the mind a new and interesting subject.

But with art it is not so, there the objects are comparatively small, and the more minutely they are examined the more numerous the faults and imperfections which we discover in them. And what is their duration? They are destroyed and forgotten, while those by nature remain for untold ages as perfect as when created. The most ingeniously and skillfully constructed machine, in the construction and perfection which man has spent many months, or years of toil and labor whose complicated mechanism, has called forth the utmost energy of mind is a toy compared with any, even the simplest works of nature. Constantly requiring repairs it grows unfit for use, and soon ceases to answer its intended purpose.

These irregulations (sic) and imperfections are present from the very first construction for no artist, however eminent can forsee (sic) all the changes which his work undergoes or be able to provide against them. The most enduring machine, the most stately edifice and the proudest works of man, last but a few years and then decay and pass [page 3] away. But not so the works of God - nothing is lost, nothing perishes in nature and though her works may disappear from the sight of man, they are not destroyed, but transformed into the objects of her handiworks, there continuing in existence.

And how many years of the results of man's ingenuity are unfit for use, serving only to amuse. It is not so in nature. There all things exist for a certain purpose, accomplishing the ends, for which they were designed and created. But God's wisdom is unlimited. The various creations which inhabit the earth and fill the air and water; the depths of space, and the many twinkling stars and planets and orbs, that hold their places in the vaults of might's dominion all proclaim the wisdom of God.

Were it granted to mortals to know the concatenation of causes in nature, how great would be our admiration!, (sic) however incapable we are of forming an inadequate idea of the whole of God's works, the little we perceive of them gives no reason for acknowledging his wisdom. But to be convinced that He is indeed wise, we need not have recourse to extraordinary events or wonderful manifestations of his skill and power, for it is proven to us in the most forcible manner by the very common occurrences, and by the daily changes which are effected in nature. Nothwithstanding (sic) [page 4] his majesty and grandeur. He does not disdain to pay attention to the weakest creature which exists, from the elephant to the mite, all animals are indebted to Him for their life, habitation and nourishment. Nature is always acting even when she appears to rest - and she renders us real services when she seems to refuse them.

We cannot turn our eyes on any side, without seeing innumerable objects which have connected with them some inseparable attribute which shows God's wisdom for whether they be great or small the skill and forming hand are His. The starry is (sic) an admirable theater of the wonder of the most High, Their (sic) multitude of splendor under them, a most magnificent spectacle, while their order and grandeur affords topics for the sublimest (sic) thoughts. What can be more beautiful and majestic than the immense expanse of the heavens illuminated by lamps without number glowing the more brightly from the darkness out of which they shine (sic). To name the immense bodies dispersed through vast space, is sufficient to excite astonishment and admiration at the majesty of the workman. In the centre of our system of worlds the Sun (sic) has established his throne, and around him at uniform distances, and in certain periods of time revolve the planets.

But the whole system including the sun and his planets, is but a point in the expanse of nature. We behold innumerable stars, which though they appear to us small, are probably equal [page 5] to the Sun (sic) in dimensions and splendor, and they may be not only worlds, but centres of planetary systems (sic). Human intellect cannot determine the design for which these bodies were created; but without doubt they have sublime ends, and each of them a suitable and particular destination and they may be inhabited as our earth with intelligent and rational beings.

However surprising these observations may be, we do not yet reach the limits of Creation. If we could dart beyond the moon and approach the planets, if we could leave the Sun behind and approach the most distant stars, we might still discover new orbs and new systems of worlds, perhaps more and more magnificent and yet these would not fix the bound of the empire of the Creator. How vast, how unlimited must be the wisdom of Him who has created these worlds and who regulates and supplies them. They have never in the course of their revolutions of thousands of years come into contact nor interrupted each others (sic) motions. The fixed stars are now relatively situated as they were thousands of years ago, their distances never varying. What power has fixed them, in their lofty place and what retains them in those positions?

It is of God the Creator of all things whose wisdom has devised means of supporting them each in its proper bounds, and [page 6] these means continue unbeknown to man, undiscovered by the sublimest (sic) genius, and they forever remain a mystery;

"But chief of all his works, since time began,

He summoned to life, and named it Man.

A wondrous frame; of dust he made the whole,

And breathed into the clay a living soul,

With intellect endered and powers of sense

To scan the wonders of omnipotence." *

There is perhaps no work which demonstrated the wisdom of God more than the Creation of Man, the perservation (sic) of his life, and the adaption of all the works of nature to his comfort and enjoyment. The millions of human beings dispersed in different nations over the earth, are provided with everything necessary to supply their wants and render life comfortable. The greater the number of men is, the more their wants are varied, according to their conditions, ages and manners of life, and the more incapable are we of forming a plan which will embrace every case of taking the necessary precautions for the preservation of life; and consequently the more should those arrangements, full of goodness and wisdom, which our Creator has made for this purpose, deserves our attention and admiration. All things teach the wisdom of God - we can cast our eyes on no side, but we are made more clearly conscious that this great attribute of Diety (sic) is upon all nature.

"What does Philosophy impart to man,

But undiscovered wonders; Let [page 7] her soar,

Even to her proudest heights, to where she caught,

The soul of Newton and of Socrates,

She but extends this scope of wild amaze

And admiration. All her lessons and,

In wider views of God's unfathomed depths."**

Anna Reynolds - College July 11th, 1846

Notes:

* "But chief of all his works, since time began,

He summon'd to life, and nam'd it Man:

A wondrous frame! Of dust he made the whole,

And breath'd into the clay a living soul;

With intellect endued, and powers of sense

To scan the wonders of Omnipotence."

Original text of the poem by Mrs. Clark's Lines on Reading Strum's Reflections (Bristol, March 12, 1801)

** "What does philosophy impart to man

But undiscovered wonders?--Let her soar

Even to her proudest heights--to where she caught

The soul of Newton and of Socrates,

She but extends the scope of wild amaze

And admiration. All her lessons end

In wider views of God's unfathom'd depths."

Excerpt from Henry Kirke White's poem entitled "Time, A Poem [1]"

Category:

8: Communication Artifact

Date:

1846

Dates of Creation:

1846

Object ID:

COMP2